CREW PATCH STORY

On this day, March 25th, 1995, VP-47’s CAC-9 in a P-3C Orion, operating out of the squadron's Oman detachment, was performing an ASW mission with the USS Constellation battle group, 200 miles east of Oman.

Upon returning, the aircraft suffered engine problems. The PPC, Lt. Jeff Harrison, experienced the worst engine failure ever to occur in the entire P-3C series of aircraft. The number four propellor had thrown a blade. They blade was thrown right to left and cut through the body of the aircraft, striking the fuselage, and severing 35 of 44 engine and flight control cables, causing a complete shutdown of all four engines.

Harrison managed to make a textbook, perfect water landing without power and with no casualties to the crew. Harrison was subsequently award the Distinguished Flying Cross for his flying expertise and acumen under difficult emergency conditions.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Second account by PPC LT Jeff Harrison

We flew back to the airfield at 16,000 feet and executed a slow, spiraling descent to maintain our number four engines rpm at 100 percent. Not knowing what would happen when we fuel chopped the number four engine, the flight station went through the descent, approach and three engine landing considerations checklists. Approaching 6,000 feet and nearing the engine's limit power setting, we decided to circle the field one last time, extend out fora good downwind leg and fuel chop the engine in anticipation for our landing. Unfortunately, we would not get to land at the airfield. Passing 5,600 feet, we heard and felt a tremendous explosion. My co-pilot, who was in the right seat, looked out and saw a huge cloud of black smoke. To his utter dismay, when the smoke cleared, he saw the number four prop missing and the reduction gear box on fire. LCDR Radice called out to shut down the number four engine and discharge the fire extinguisher.

I was in the left seat, so I was unable to see what was going on. Trusting his judgment, I concurred with the decision to shut the engine down. The flight engineer shut down the engine and discharged the fire extinguisher. LCDR Radice looked out at the engine and the fire was still raging. AE1 Richard Willhite then discharged the second fire bottle. Unfortunately, the fire kept burning. AE1 Richard Willhite then called out that the number three engine's rpm was winding down. LCDR Radice looked out at the number three prop and called out that the prop are looked bad. It made sense that during the explosion, the number four engine probably took out the number three engine. We then called out to shut down the number three engine. While the flight engineer was pulling the number three emergency shutdown handle, I simultaneously advanced the number one and number two engine power levers.

Expecting to hear or feel a pitch change in the prop and not getting one, you can imagine my reaction when I looked out and saw both props barely rotating. Upon seeing this, I looked back inside the flight station to let the rest of the crew in on the secret, but AE1 Richard Willhite beat me to it and called flameout on number one and two engines.

All of the sudden the flight station went dark due to a total electrical power loss. Shaking my head with dismay, "saying you've got to be kidding me," we directed AE1 Richard Willhite to pull the hydraulic boost handles and start the auxiliary power unit in order to get electrical power back. At this time we were gust locked, which is the same as when your car's steering column locks up and you can't move it. To say the least, it was not a good feeling. After the boost handles were pulled, the flight engineer made several attempts to start the APU, but it kept flaming out. At this point things were really looking bad for VP-47's crew. When the boost handles were pulled, the aircraft should have switched from a hydraulic to a mechanical advantage. For some reason, this didn't occur and we were unable to control the aircraft. The aircraft rolled right into a 45-50 degree angle of bank and our airspeed bled off from 260 to 210 knots.

On the flight station we thought that the aircraft was going to stall and roll inverted. What a horrible gut wrenching feeling it was to think that this was going to be the end for everyone. I was their aircraft commander and I as responsible for their well-being. I could not get control of the aircraft and we did not have time to put on our parachutes to bailout. Even if we would have had time to don our parachutes, the main cabin door was facing the sky, which made bailing out impossible.

Up to this point, the entire evolution from engine explosion had taken about 45 seconds. With my heart pounding from being afraid and wanting to save the rest of the crew, I said a quick prayer. My prayers were answered. The control column went boost out and unlocked. Finally at about 2,500 feet, we were able to control the aircraft. We leveled the wings, then continued in a left hand turn to acquire the airfield. When I saw the airfield 90 degrees off of our left wing, we were at 2,000 feet and 6-7 miles away from land. A harsh reality set in -- we were going to have to ditch the aircraft.

Having never heard of or seen NATOPS procedures for a no engine, no-flap, boost-out ditch, the we had to use gut instinct. We knew that if we flew too fast, it would be hard to pull the nose up upon water entry. If we flew to slow, the aircraft would stall soon after leveling off above the water. We maintained our airspeed between 175-180 knots, which gave us a 1,000 fpm rate of descent. At this time, as with all life threatening situations, each crew 7 member's adrenaline system kicked in to its maximum. Fortunately, I had a great set of parents and a high school football coach who was a former Oakland Raider all-pro football player who taught me to never quit and find ways to win. At about 1,200 feet, we told the rest of the crew to prepare for immediate ditching. At 200 feet approaching water entry, both LCDR Radice and I started pulling back on the yoke. The nose came up nicely. The two biggest items necessary to perform a successful ditch is to maintain wings level and have a shallow rate of descent. At first, we were able to keep our wings level and get our rate of descent to about 300 feet per minute. At 80 feet, the right wing started rolling as we slowed down. LCDR Radice recognized the problem, called for left full yoke and the right wing came back up. Upon water entry, we were wings level, had a 200 feet per minute rate of descent and were right at 135 knots. After several skips across the water and fighting to keep the nose of the aircraft up, the plane finally came to rest. A P-3 ditch can best be described as being similar to a log ride at an amusement park, but with more of a kick in the pants.

The amazement of still being alive with the Orion still afloat caught me off guard, but there was little time for celebration. The water traversed through the tube of the aircraft and shot into the flight station like someone pointing a fire hose at us. My co-pi lot and flight engineer evacuated the aircraft through the overhead escape hatch. I evacuated the aircraft through the side escape hatch located immediately behind the pilot seat on the left side. After jumping into the water, I soon realized that the plane was still drifting like a boat does without power.

To my chagrin, the number two prop was coming right for me and was going to plow right over me. All that 1 could do was to paddle backwards as fast as I could to avoid the prop, putting my hands on the prop to push me out of its way. Fortunately, the aircraft came to a stop and I was able to swim to the leading edge of the wing between the number one and number two engines. I called out to LCDR Radice to see if the whole crew made it out of the aircraft. I was covered from head to toe with aircraft fuel and my eyes were on fire. My flight gloves were slippery from the fuel and this made it difficult to climb on top of the wing. After three tries, I was finally able to climb on top of the wing and reach the my TACCO and in-flight technician. The rest of the crew evacuated out the starboard side escape hatch and entered their life rafts. My in-flight tech nician was pulling the ring to inflate the life raft, but the blasted thing would not inflate.

A pilot friend of mine and his crew were waiting to take off to pick up an admiral in Bahrain when we hit the water. Shortly after we got into the life rafts, my buddy flew over and the crew let out a big yell. Once things finally settled down, the crew looked each other over and checked for injuries. To my surprise, not a single crew member was injured. The only person with a problem was me.

Up to this point I had controlled my temper quite well, but this was too much. After a few choice words directed to the life raft, the only option left was to inflate our life vests and swim around to the other side. Realizing our predicament, the crew in the other life rafts began to paddle around the rear of the aircraft in order to meet us. The three of us joined the other crew members and climbed into the rafts.

I had fuel in my eyes and they were burning like crazy. My sensor one operator carried a little water bottle in his life vest. He pulled out the water bottle and began to pour it in my eyes to flush out the fuel. While he was taking care of me, my TACCO and second pilot were trying to contact the other P-3 crew on our PRC-90 radios to let them know of our status.

This day was true to form, because my TACCO went through three radios before he found one that worked. On the fourth radio, he was finally able to talk to the other crew to let them know that we were fine.

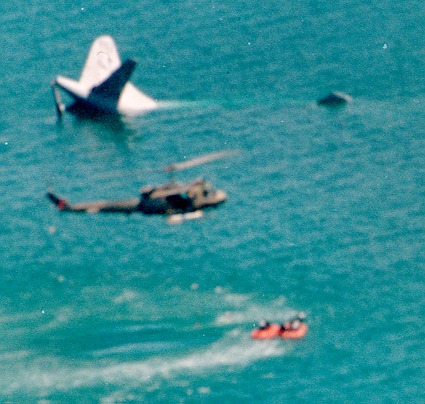

We were in the rafts for only 10 minutes before the SAR helicopter arrived. The rescue was uneventful. The helicopter took seven crew members on the first trip and four crew members on the second trip.

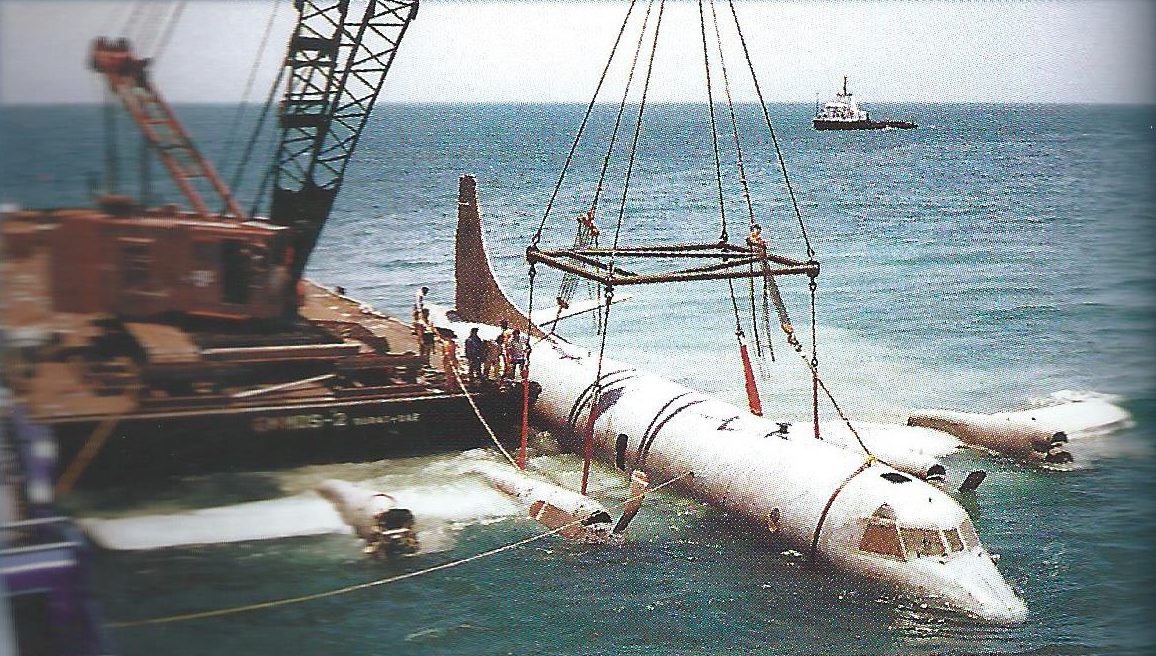

A month later, a barge and crane raised the aircraft and we discovered that the number four prop had thrown a blade. The imbalance of only three blades caused the engine to explode. The prop blade was thrown from right to left and cut through the body of the aircraft, severing 35 of 44 engine and flight control cables. Four of the cables cut went to the four engines. The cutting action caused a pulling action which shut down all four engine simultaneously. The hydraulic boost handle cables were cut and the APU fuel line was cut. The nine intact cables were two aileron cables, two elevator cables, two elevator trim tab cables and two rudder trim tab cables.The co-pilot's main flight control cable was cut. VP-47's crew nine flew under a lucky cloud that day.

For so many things to So wrong and everything to work out perfectly was a total surprise to me. I have never questioned the reason we were spared, but I am glad that we were.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Third Account

Following story by LT Wes Smith for an Approach Mech Article July-August 1996

Our aircrew had flown two days of ASW events with Constellation battlegroup. During the trip home, after five months of surveillance missions in the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea. I was sitting in the galley, writing a post-mission report when the flight station called me (I was TACCO) to my station.

“We have a prop-pump light on No. 4 engine, “he said.

The pilot wanted me to help the nav/comm report our problem to homeplate at Masirah, Oman. The nav had everything under control, so I simply monitored his comms. I tried to gain more information form the flight station without interrupting their troubleshooting.

It seems they were worried about having a pitchlocked prop. They planned to wait until we were overhead Masirah to descend. The 2P was a second tour, former FRS instructor, who had reported to the squadron less than a month before. He told me there might be quite a bit of adverse yaw whenever they shut down the engine.

Because were close to our landing side and expecting adverse yaw, I decided to have the crew set Condition 5 (strap in and secure all loose equipment) before we started the descent.

As we were descending, we continued talking to our maintenance department on base frequency. Our pilot NATOPS officer made a comment I’ll always remember. In his classic Arkansas twang, he said, “It sounds like y’all have everything under control.” At the time, I thought we were prepared for a three-engine landing in Masirah.

As we passed 6,500 feet, I heard a loud explosion, followed by the sound of metal tearing through metal. I will never forget the next thing I saw. The nav looked at me with fear in his eyes and yelled, “Wes, we’re on fire!”

I glanced at my station. There was no electrical power. That didn’t stop the nav from calling “Mayday, Mayday. We’ve lost No. 4!” Our maintenance control, the Omani Air Force Tower, and SAR alert heard him before we lost all power.

I then secured all station equipment, hoping it would make it easier for the flight station to restore power. As I looked to my left, I could see that the No. 1 and No. 2 engines were windmilliing, winding down from a loss of power. The 2P yelled, “Immediate ditch, immediate ditch!”

We were already strapped in. All I had to do was put on my helmet and tighten my straps.

It was about a minute and a half until we hit the water. I said a prayer, thought back to my last phone call with my wife and considered what I was going to do once we hit the water. We were only six miles from land, and all I would have to do to survive was get out of the aircraft after we hit.

We skipped three times on the water before stopping. I was immediately grateful for all our drills and my water-survival training as I went through my emergency actions without thinking. My most vivid memory is the rush of water crashing through the tube. My first impression was that the plane was sinking fast.

I left my seat and started toward the port over-wing exit. There was enough light in the tube that I could see the other crew members moving toward the exits, but I couldn’t tell who was who. The only damage I could see in the interior was a door from one of the C racks floating in the water and a loose door on one of the B racks. I had no problem walking back toward the exit.

At this point, the water was 18 to 24 inches deep in the tube. There was a small traffic jam at the starboard over-wing exit, and I actually considered using that exit, but I knew the port over-wing was my assigned exit. Besides, it would cause confusion later if I took the wrong exit.

I met the flight tech at the port over-wing exit. He had already removed the hatch and was throwing the raft out the door. The flight tech told me that he had handed the door to me, but I don’t remember what I did with it. I followed him out the hatch and was greeted by the PPC standing waist deep in water on the wing between the No. 1 and No. 2 engines. He had used the side escape hatch in the flight station. The flight tech was struggling with the inflation handle and couldn’t get the raft to inflate.

The 2P was walking along the top of the fuselage counting heads. I asked him if everyone was out. He assured me they were and that the other two rafts were inflated on the other side of the sinking aircraft.

The PPC suggested we swim to the other rafts and then reminded me to inflate my LPA. I had been so caught up in worrying about the other survivors and the challenge of inflating the raft that I had forgotten it. I waded off the wing. Then the PPC, flight tech and I attached our LPAs together and began to backstroke around the aircraft toward the other rafts. As we swam around the aircraft, I got an excellent view of the broken MAD boom dangling from the tail. There were also numerous sonobouys marking the aircraft’s trail through the water, their red flags were surrounded by suspension packages.

When the other crew members saw us swimming towards them, that started paddling toward us and helped us board the raft. Fortunately, seas were calm.

Apparently, there were uncertain about our fate and were glad to see us. I vividly remember the radar operator saying, “Everyone is OK, sir!”

As I climbed in the raft, I saw the P-3 on the horizon flashing its landing light and flying towards us. The other crew had seen us hit the water and took off immediately for the SAR effort.

When everyone was safely in the raft, we checked each other for injuries or signs of shock. The PPC had fuel in his eyes, so the acoustic operator used a water bottle to flush then. I noticed several crew members using their PRC-90 survival radios. I told everyone except the nav to put theirs away so that only one person would be communicating with the SAR aircraft. The nav still had trouble contacting the SAR plane.

Before we could troubleshoot the problem, we saw an Omani helicopter. We decided to put away the radios and prepare for pickup. Once the helo arrived, we decided the jr man should go first. The SS-2 exited the raft and was immediately blown away by the rotor wash from the helo. Since the Omanis use a different type of horse collar than we do, the SS-2 had difficulty putting it around himself. After a short delay, the Omani SAR swimmer jumped into the water to help him. We learned later the swimmer had been reluctant to dive in because he had spotted several sharks in the area.

Each member of our crew jumped into the water in successions, was blown away from the raft by rotor wash, and got hoisted into the helicopter with the swimmers help.

After the fifth or sixth person was picked up the swimmer motioned for us to stay in the raft. He swam to the raft and told us to stay in the raft for the next pickup, contrary to what we were taught during water survival. The helo took one more person and had to return to base to drop off the survivors, which left the FE, the nav, the 2P and me in the raft.

I turned on my PRC-90 and was able to establish comms with the SAR plane. I told them no one was hurt. The Omani helo returned and picked us up for the short flight back to Masirah.

The best lesson I learned from this mishap is that training is everything. My old PPC has insisted on holding at least one drill every flight. When he left the crew and I became the mission commander, I continued the practice on every flight. After the plane hit the water, all my actions were instinctive. I used the same hand holds I had used in every drill.

Incidentally, no one on the crew carried their assigned emergency gear with them. I was supposed to carry the first-aid kit and the port water bottle, but being so close to land, I focused on safely egressing the aircraft, not an extended survival situation.

During my water-survival training in Pensacola (and subsequent refresher), I had thought the helo dunker was not very beneficial, since I am a helo passenger less often than most surface warfare officers. But the training I received in the helo dunker was invaluable. After egressing an upside down helo blindfolded, leaving a right-side up P-3 in daylight was not that hard.

I also learned that not everyone operates the same way as our Navy. From now on, when I fly where organizations other than the Navy or Coast Guard are responsible for SAR, I familiarize myself with their SAR procedures.

Comments

There are no comments yet.

Be the first to tell your patch story!